A Woman of Courage

Asiaweek, 25 October 1991

The telegram came from the Norwegian capital of Oslo, and it was addressed to Senior Gen. Saw Maung, head of Burma's ruling State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC). What the junta boss thought of it can easily be guessed. The Oct. 14 telegram asked Saw Maung to pass a copy of the Norwegian Nobel Committee's citation to this year's Peace Prize winner: Burma's opposition leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, It's unlikely he did.

The committee sent the message to Saw Maung because it was unable to contact Suu Kyi. She has been under strict house arrest in Rangoon since July 1989. Said the citation: "She became the leader of a democratic opposition which employs nonviolent means to resist a regime characterized by brutality." The committee, composed of Norwegian parliamentarians, added that it wanted to show support for people throughout the world striving to attain democracy and human rights by peaceful means.

It was not the first time that the Peace Prize has been used to make a political point. In 1989 it went to the Dalai Lama, exiled spiritual leader of Tibet. That nomination came just four months after China's crackdown on pro democracy protests in Tiananmen Square. This year's award was particularly poignant: no one could say for sure whether the embattled Suu Kyi, 46, was even aware that she had received the honour. Her husband, British academic Michael Aris, had not spoken with here since July. But, said a U.S. embassy spokesman in Rangoon: "She should know. She's a pertty smart lady."

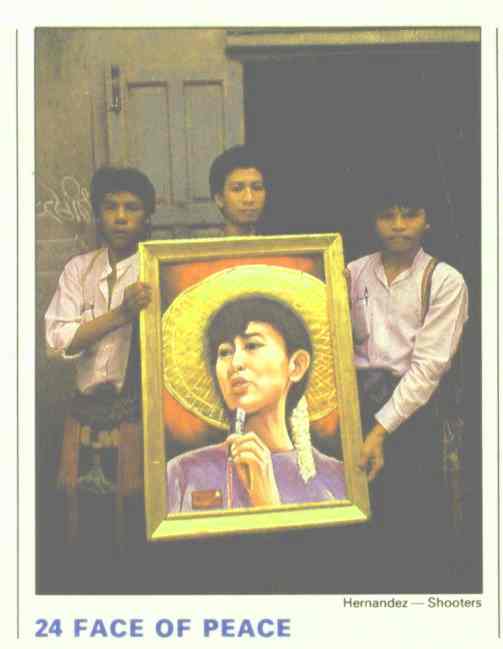

Her courageous stand against Burma's military regime has impressed the world. Suu Kyi was honoured with a string of awards this year, among them the European Parliament's human rights award and the Sahkrov prize for freedom of thought. But the Nobel Prize was the most pointed snub yet against a regime that stubbornly clings to power against the will of the people. Although Suu Kyi's National league for Democracy won an overwhelming victory in May 1990 elections, the military has refused to hand over power to a civilian government.

The award will undoubtedly boost the morale of Burma's decimated prodemocracy forces. chao Tzang Yanghwe, Burmese author and Son of the country's first president, feels it will have a "tremendous impact" in Burma. "There's no way SLOR%C can handle this," he says. "It will embolden the people. It will create repercussions within the army."

Suu Kyi is unlikely to go to Oslo to receive the $1 million prize. The junta says she will be released from house arrest if she renounces politics and leave the country. She has refused, saying she won't quit Burma until a civilian government is formed. So she remains in isolation in a two-storey house on university Avenue in Rangoon facing Inya Lake. Outside, armed soldiers keep a 24 hour vigil. Across the lake stands the spacious and heavily guarded home of retired Burmese strongman Ne Win, who is widely believed to be still influencing events in the country.

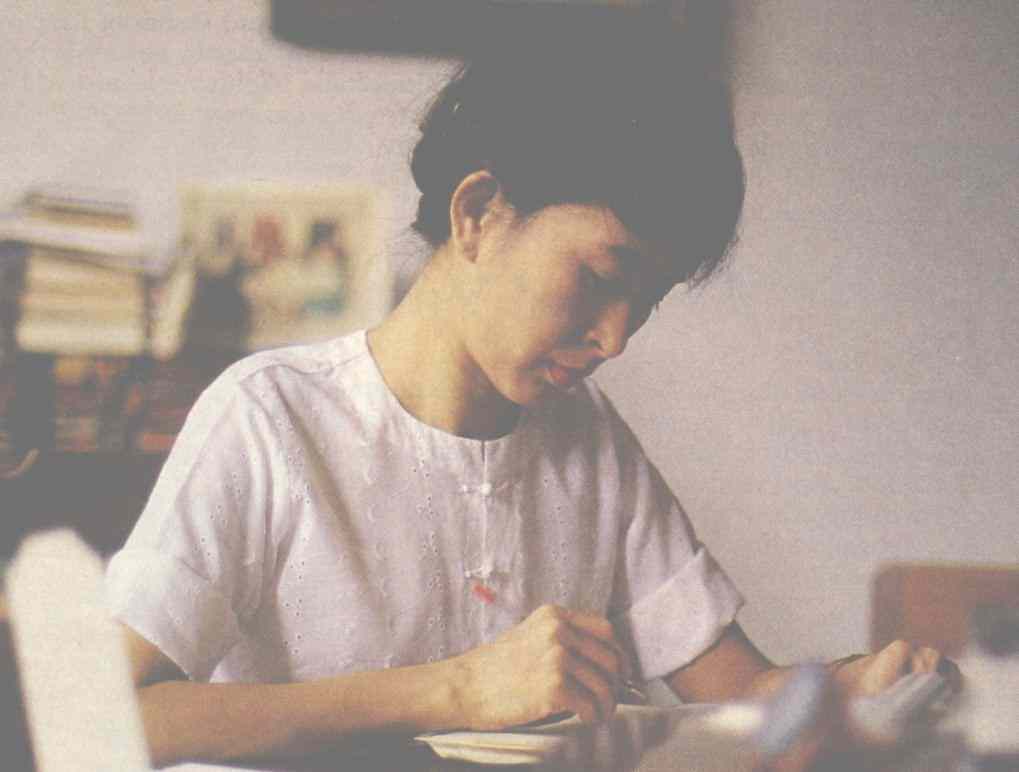

The last time Suu Kyi saw her husband and two sons was in December 1989. Aris, a British citizen, is now a visiting professor of Tibetan and Himalayan studies at Harvard University in the U.S. Their sons Alexander, 18, and Kim, 14,attend boarding school in Britain. Before her house arrest Suu Kyi would receive visitors in a large front room that served as her office. An assistant sat in an adjoining room looking out on to a covered porch where visitors waited patiently to be admitted through a flyscreen. Often students would sit there smoking cherroots and registering new members the NLD. In the back was a fenced garden where Suu Kyi liked to feed the crows in the quiet of the morning. Since her arrest she has refused to accept donations from friends in Burma and abroad, and reportedly had to sell her piano to make ends meet.

Predictably, the regime has tried to ignore Suu Kyi's award. Burmese state radio and television made no mention of it. But there was "a palpable buzzing in the streets" on Oct. 14, said one foreign observer. "People probably did find out pretty quickly about the honour from foreign radio broadcasts," he said. Officials at the Burmese embassy in Bangkok had been instructed to reply "no comment" to queries on the award, second secretary Mya Tun told Asiaweek. "That's our official position." Burma's ambassador to Thailand was quoted as saying the Nobel Committee had not made a good choice. The award came at a time when the junta was tightening its grip with a purge of the educated middle classes and civil servants.

It was almost by accident htat Suu Kyi became involved in her country's democracy movement. The daughter of assassinated Burmese independence hero Aung San, she left Burma at 15 when her mother became ambassador to India. She studied in India and later at Oxford, where she took a degree in politics, philosophy and economics. It was there she met her husband. Though intrigued by Mahatama Gandhi's philosophy of non-violent protest, she stayed out of Burmese politics till 1988. In April that year she left Oxford to care for her dying mother in Rangoon, just as massive anti military protests gathered steam. Three months later Ne Win, who had ruled Burma for 26 years, was forced to resign. But the military remained in power, and killed thousands of Burmese in ensuing popular uprisings.

Suu Kyi began speaking out against the military and soon became the leader of the strongest party in the pro-democracy movement, the National League for Democracy. She was a tireless campaigner, traveling to distant parts of the country despite intimidation and harassment by the military. Her goal, said the Nobel committee, "was a democratic system of government in which all the regions and ethnic groups would be presented." At first the army did not move against Suu Kyi personally, though it issued martial law orders prohibiting gatherings of more than five people and banned public criticism of the regime. In July 1989, however, it placed the charismatic leader under house arrest.

Perhaps underestimating the strength of the democracy movement, the military kept its promise to hold parliamentary elections in May 1990. Though Suu Kyi was unable to campaign, the NLD won 392 of the 485 seats contested. The came the hijack of Burmese democracy -- the junta, lead by Saw Maung, refused to give up power. The junta has since made it clear that it will have the dominant say in a proposed constitution, and has arrested many NLD members, forcing others into exile. According to a recent report by the London-based human rights group Amnesty International, which won the 1977 Peace Prize, "the military arrest people everywhere -- in homes, buses, cafes -- and have relentlessly tortured government critics. Hundreds of people have simply vanished into the prison system."

In the face of such tactics, the petite Suu Kyi has nothing to rely on but her courage. "She is the bravest person in Burma," says Tzang Yawnghwe. Burton Levin, U.S. ambassador to Burma at the time uprising, says "she is willing to sacrifice her personal life and herself for the cause of restoring freedom and a better life to the Burmese people." Adds Levin: "Everything projects her as fighting for the Burmese people. They recognize that and flock around her because of it."

While condemnation of the regime has been strong in the West, Burma's closest neighbours have been much more muted in their criticism. But the Nobel award will have an effect on them, too, says Josef Silverstein, an author of several books on Burma. It will really pressure the ASEAN countries to reconsider the decision they took earlier this year [not to impose economic sanctions on the regime]."

Despite the military's repressive tactics, the six ASEAN nations, China, Japan and South Korea continue to trade with Burma. china is one of the regime's biggest arms suppliers, and Thai contracts for logging and fishing rights are another important source of income. Japan, which cut off aid to Burma after the bloody 1988 uprising, restored it after the 1989 elections, and is now the country's largest aid donor and a major trading partner. On Oct. 15 Japanese Cabinet Secretary Sakamoto Misoji remarked that Suu Kyi's house arrest was "unpleasing." The Nobel award, he said, showed "the increasing interest of the international community in [Burma's] democratic reform."

In Bangkok, Thai foreign Minister Arsa Sarasin said the Nobel award would not affect relations between Bangkok and Rangoon. "As long as Thailand and Burma are situated in the same region, we cannot avoid each other." Prime Minister Anand Panyarachun called the award a "personal honour" for Suu Kyi but said his government would not send her a congratulatory message because she did not "represent the Burmese government."

In marked contrast to regional reaction, the White House in Washington issued a statement praising Suu Kyi's "courage and sacrifice," calling it "an inspiration to all who believe in democratic principles and government." Even U.N. Secretary-General Javier Perez de Cuellar, who is rarely critical of U.N. member-state on politically sensitive issues, said he was "pleased" to learn of the award. "The secretary-general has repeatedly appealed on her behalf with the authorities in [Rangoon] and he hopes that this international recognition will lead to her earliest release from house arrest," a U.N. statement read.

Burma scholar Silverstein thinks foreign pressure is crucial for change. The Burmese people themselves could not do it alone, he says, "because they are held hostage; 40 million people with 200,000 guards." Levin hopes "that Suu Kyi getting the prize will arouse recognition even within the military that the present government is leading Burma down a dead end, making them a pariah nation and causing the people suffering." The fear is that things may have to get worse before they get better.

ASIAWEEK/25 OCTOBER 1991